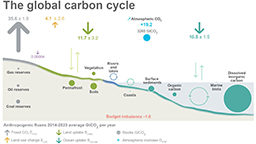

Above graphic: This infographic depicts the global carbon cycle, annual flows of carbon into the atmosphere and portions absorbed by the ocean and land for the decade 2014–2023 in billions of metric tons per year. The budget imbalance is the difference between the estimated emissions and sinks. Source: NOAA-GML; Friedlingstein et al 2024; Canadell et al 2021 (IPCC AR6 WG1 Chapter 5); Global Carbon Project 2024

Emissions of carbon caused by fossil fuel pollution continued to grow slightly in 2023 to 36.8 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide, setting yet another new record despite increasingly urgent warnings from scientists about the need for steep and immediate decreases.

Preliminary estimates compiled by the Global Carbon Budget project indicate that the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) released into the atmosphere by fossil fuels will increase by another 0.8% in 2024, which would raise yearly emissions to 37.4 billion metric tons of CO2.

“The impacts of climate change are becoming increasingly dramatic, yet we still see no sign that burning of fossil fuels has peaked,” said Pierre Friedlingstein, of University of Exeter’s Global Systems Institute, who led the study. “Until we reach net zero CO2 emissions globally, world temperatures will continue to rise and cause increasingly severe impacts.”

The Global Carbon Budget is an annual report that tracks changes in how much carbon is emitted to the atmosphere and how much is absorbed by carbon sinks such as terrestrial plants, soils, and the ocean. Roughly 25% is absorbed by the ocean and just under 30% by land ecosystems. The rest remains in the atmosphere, where it continues to trap heat for hundreds of years.

NOAA provides about a quarter of all the atmospheric CO2 observations and about half of all the surface ocean CO2 observations used in the analysis. Several NOAA scientists are co-authors.

At current rates, the report estimates, there’s a 50% likelihood that global average air temperatures will regularly exceed the 1.5-degree Celsius target (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) by 2031. That’s the target scientists have identified as a threshold which avoids the most severe impacts of climate change. If emissions are not curtailed, a 2-degree Celsius increase (3.6 degrees F) could happen by 2052, they said.

The latest data reflects gains realized from widespread adoption of electric cars and renewable energy displacing fossil fuels, as well as decreasing emissions from deforestation. The United States is one of 22 countries whose fossil CO2 emissions decreased during the past decade (2014-2023) while their economies grew. That was largely counterbalanced by increases from other countries, like India and China, which have stalled a change in the trajectory of emissions towards net zero.

The findings were announced at COP29, the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Baku, Azerbaijan.

The Global Carbon Budget relies on data from NOAA’s Global Greenhouse Gas Reference Network as a primary source for estimating emissions and atmospheric CO2 levels. The Global Monitoring Laboratory’s CarbonTracker global model of atmospheric CO2 is one of the models used to help estimate global sources and sinks. NOAA will be expanding atmospheric measurements following a recent agreement to fly sensors on a commercial jet liner to track emission sources from large metropolitan regions of the United States.

NOAA also provides roughly half of all the surface ocean CO2 observations, collected from hundreds of sensors primarily on ships and moorings, but more recently also from autonomous surface vehicles sponsored by NOAA’s Global Ocean Monitoring and Observing program, which are included in a global database used to calculate the ocean carbon sink.

These evolving baseline measurements are essential for understanding the amount of carbon emitted to the atmosphere and the amount removed by carbon sinks such as terrestrial plants, soils and the ocean.

Globally, atmospheric CO2 concentrations are estimated to have increased by 2.8 parts per million during 2024 and reached 422.5 ppm, 52% above the preindustrial level of around 278 ppm in 1750. The average global atmospheric CO2 concentration in 2023 was 419.3 ppm.

Why did the land sink shrink in 2023?

In 2023, the land sink absorbed 8.4 billion metric tons of CO2, 5.6 billion metric tons lower than in 2022. That represented a 41% decline over 2022 and the lowest estimate since 2015. The reduced sink was in response to the 2023 El Nino event that led to drought conditions and contributed to the large wildfires in the northern hemisphere. The preliminary estimate for the 2024 land CO2 sink suggests a recovery to around 11.9 billion metric tons of CO2 following the end of El Niño by the second quarter of 2024.

Over the past 25 years, the land CO2 sink increased during the 2014 to 2023 period primarily in response to rising concentrations of atmospheric CO2, though with large year-to-year variability.

What’s happening with the ocean sink?

Understanding how much carbon the oceans absorb every year is critical to understanding the carbon budget. Since 1850, the global ocean is estimated to have removed 26% of total human-caused emissions, or roughly 681 billion metric tons of CO2, with more than two thirds of this being taken up since 1960.

In 2023, the ocean absorbed an estimated 10.6 billion metric tons of CO2, a small increase over 2022, in line with the expected sink strengthening from the 2023 El Nino conditions. The report projects an ocean sink of 11 billion metric tons for 2024, again slightly higher than the previous year and consistent with El Nino to neutral conditions.

In respect to ocean work, one thing is becoming more clear: ocean carbon uptake is driven by rising atmospheric CO2, said Rik Wanninkhof, an oceanographer with NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory in Miami.

“The ocean and land are providing a service by being a natural sink for anthropogenic CO2,” Wanninkhof said. “So far the ocean sink has kept pace with increasing atmospheric CO2. Will it always be that way, particularly if fossil fuel emissions are curtailed? It appears that the ocean is losing some of its ability to take up CO2 due to changes in ocean currents, biology and buffering capacity. We need to be tracking the ocean sink to understand that.”

But as the ocean absorbs more CO2, it comes with a cost, said Richard Feely of NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory in Seattle.

“Recent studies have demonstrated that ocean acidity is increasing at a rate of about 4% per decade, which is much larger than any time over the past 4 million years,” Feely said. “Combined with increasing ocean temperatures, these human-caused changes are having significant negative impacts to critical marine ecosystems and important fishery resources that provide major contributions to the long-term food security of our planet.”

To learn more about this year’s Global Carbon Budget report, visit: https://globalcarbonbudget.org/