A new report from the Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy, in partnership with the International Arctic Research Center and the University of Alaska, Fairbanks, describes major changes in temperature, sea ice, glaciers, permafrost, plants, animals, and oceans the past five years.

The report, Alaska’s Changing Environment, will be updated every three years.

This first installment focuses most of its attention on the dramatic changes Alaska, the fastest warming state in the U.S., has experienced in just the last five years.

Unlike the National Climate Assessment reports issued by the U.S. Global Change Research Program, Alaska’s Changing Environment can pay more attention to topics that are relevant to Alaska alone; for example, it devotes two pages to sea ice trends. In addition, the new report brings Alaska climate observations up to date through August 2019. (The Fourth National Climate Assessment, published in late 2018, contains no information beyond 2016 for Alaska).

Rick Thoman and John Walsh of the Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy authored the report. Some of the content comes from Walsh’s own research—partially funded by the Climate Observations and Monitoring program at NOAA’s Climate Program Office—in which he developed climate indicators to monitor variables like tundra greening, growing season warmth, storminess, and sea ice.

“Our hope,” said Thoman, Alaska Climate Specialist, in a recent interview with Climate.gov, “is that the style and presentation will allow any interested citizen to get a feel for what’s been happening in recent years. By focusing solely on observed changes (or lack of changes), we avoid the confusion that can result in mixing ‘what’s happened’ with ‘what might happen’ through climate model projections.”

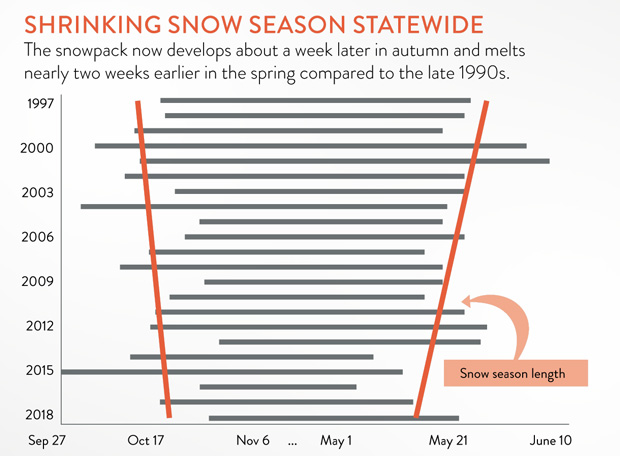

Another feature of the report is its anecdotal observations from rural areas of Alaska. Climate change threatens dire consequences for many Alaska Native villages in remote areas, where subsistence hunting, fishing, and gathering are critical to livelihoods. On April 7, 2017, Miki Collins of Lake Minchumina observed that the snow melt was earlier than usual. “Dog team hauling gas during spring melt,” said Collins in the report. “Gravel exposed on Holek Spit grinds on sled runners, a problem especially when hauling heavy loads.”

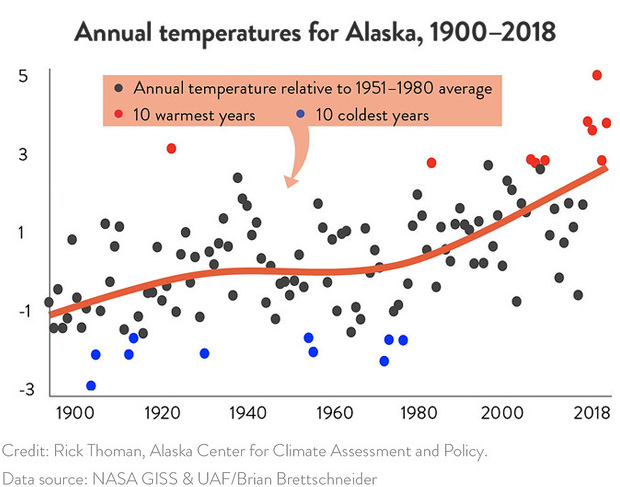

Alaska has been warming twice as quickly as the global average since the middle of the 20th century. Alaska is warming faster than any U.S. state. Alaska’s Changing Environment notes that, since 2014, there have been 5 to 30 times more record-high temperatures set than record lows.

On July 4, 2019, all-time temperature records were set in Kenai, Palmer, King Salmon, and Anchorage International Airport. Remarkably, Anchorage hit 90 degrees Fahrenheit; the average summer temperature in Anchorage is normally in the mid-sixties. July 2019 was the hottest month in recorded history for the state. June 2019 was the second warmest on record.

Length of the snow season (gray bars) in Alaska each year from 1997-2018. Orange slanting bars show the trend: the date when the state becomes 50 percent snow covered is arriving a week later in October than it used it, and the spring “snow-off” date—when half the winter snow has melted—is arriving nearly two weeks earlier. Image by Rick Thoman, Alaska Center for Climate and Policy.

These extremes on land are surpassed by what’s going on in the sea. The report says, “Nothing in the Alaska environment is changing faster than sea ice.”

Today, typical summer ice extent on the Chukchi Sea is only 10% of what is was in the early 1980s, and the Beaufort Sea ice-over usually occurs two to three weeks later in the fall than in past decades. In 2018 and 2019, late winter ice coverage in the Bering Sea’s Alaska waters was significantly lower than any winter in the last 170 years. Surface waters along Alaska’s west coast were 4–11ºF warmer than average this summer.

The report says Alaska climate monitoring is critical to U.S. economic strength. Alaska’s commercial fishing industry is the most productive such industry in the United States, producing more harvest volume than all other states combined. Alaska exports annually more than one million metric tons of seafood; in 2016, Alaska seafood was sold in 105 countries. The Alaska seafood industry generates $12.8 billion in annual economic output for the U.S.

Climate change and ocean acidification put all the state’s fisheries at risk.

Climate change over the long term could also burden Alaska with significant adaptation costs. According to the Fourth National Climate Assessment, the cost to the state of a warming climate is projected to range from $3.3 to $6.7 billion, between 2008 and 2030 (2015 dollars).

The costs in the transportation sector alone will be significant. Greater snow and ice melt will lead to increases in transportation cost, as ice roads must be replaced with gravel roads. A 2004 report estimated the cost of gravel roads on the North Slope of Alaska at as much as $2.5 million per mile (2015 dollars).

“Alaska is built for seasonal cold,” said Thoman. “Whether it’s modern housing, transportation in the vast roadless areas of the state, or traditional food storage methods, warming is disruptive and brings stress, risk, and hardship to many.”